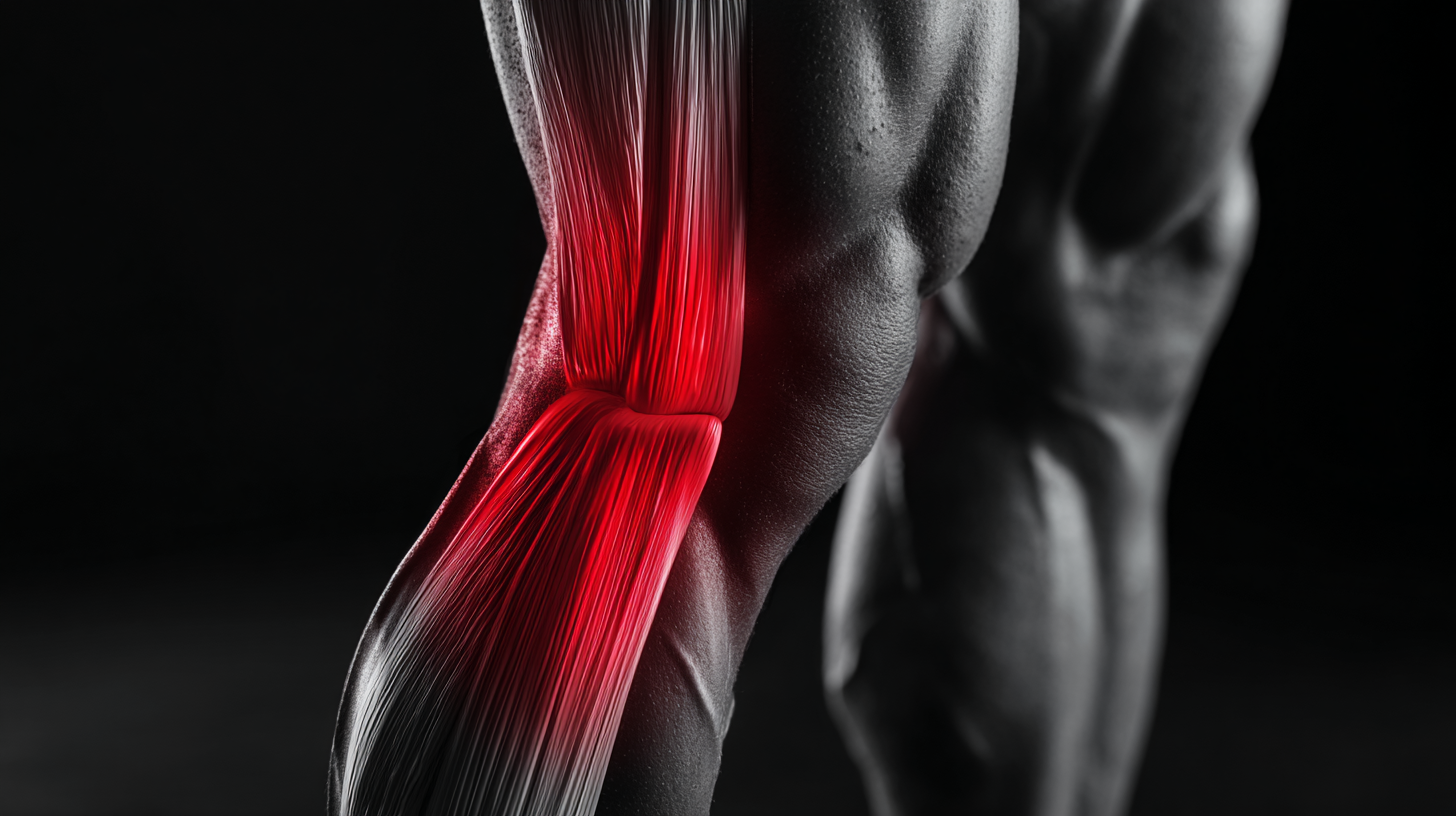

Hamstring Strain

A hamstring injury is one of the most common injuries in sport. It occurs when you strain or ‘pull’ the group of muscles at the back of your thigh. This is most often due to over stretching or overloading them beyond their limit. A Hamstring strain often occurs during sudden, explosive movements or in sports that involve sprinting with sudden stops and starts. Although hamstring strains heal quickly, they are often not rehabilitated or strengthened to their optimal level. . Re-injury is therefore very common and one of the biggest risk factors for a future injury is a previous hamstring strain.

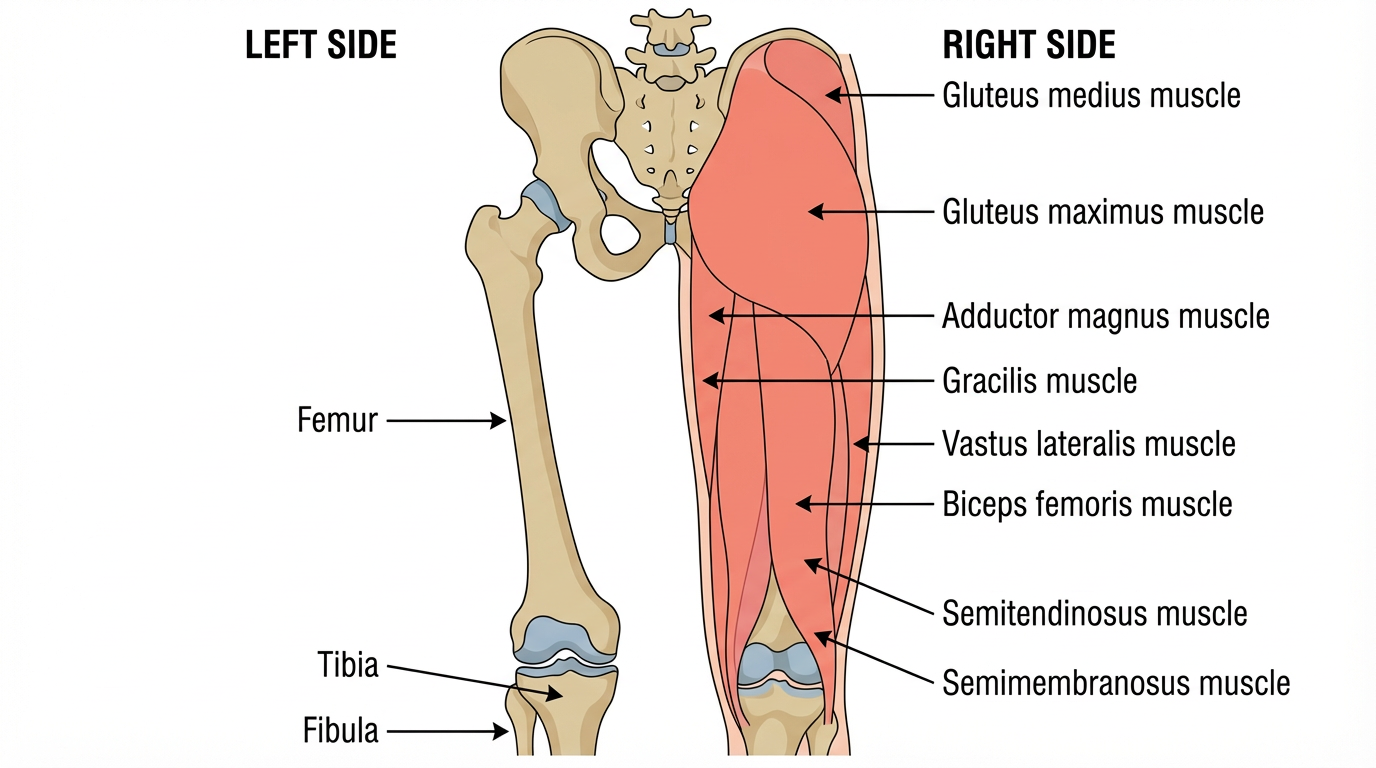

The Hamstrings

The collective term ‘hamstrings’ refers to three separate muscles located in the posterior compartment of the thigh:

Biceps Femoris

Semitendinosus

Semimembranosus

The hamstrings cross both the knee and the hip joints and are involved in knee flexion and hip extension. They are also an antagonist to the big anterior thigh muscles, the quadriceps, and control deceleration of knee extension. The biceps femoris is most commonly injured, followed by semitendinosus. Semimembranosus injury is rare.

-

A hamstring injury can occur if any of the tendons or muscles are stretched beyond their limit. They often occur during sudden, explosive movements, such as sprinting, lunging or jumping. But they can also occur more gradually, or during slower movements that overstretch your hamstring.

-

While hamstring injuries can affect anyone, certain factors significantly elevate the risk of occurrence and recurrence. The primary predictor of future trouble is a previous hamstring injury, where a higher severity of the initial tear leads to a greater chance of it happening again. Age is another significant contributor, with those 25 and older facing a five-fold increase in risk. Physical history also plays a role; other lower limb injuries, particularly ACL damage, can predispose an athlete to hamstring issues. Beyond history, physiological factors such as muscle weakness and strength imbalances—specifically a high quadriceps-to-hamstring strength ratio—are leading indicators of vulnerability.

Furthermore, the risk is compounded by mechanical and lifestyle variables. Fatigue and overload from overtraining without rest, as well as poor movement patterns regarding stride length and cadence, place undue stress on the muscle fibers. Reduced flexibility, whether originating in the muscle itself or through neural pathways like the sciatic nerve, further limits the muscle's resilience. Finally, preparation is key; an inadequate warm-up leaves muscles stiff and less adaptable, while dehydration makes them more prone to cramping and subsequent injury.

-

Depending on initial severity and location of a hamstring injury, a person can be significantly debilitated and be forced to take extensive time away from activity. Most people who suffer an acute hamstring strain will experience some of the following:

Sharp pain at the back of the thigh or buttocks occasionally accompanied by an audible or palpable “pop” and a sensation of the leg giving way.

Difficulty moving and weight bearing. Following a hamstring injury, it may be hard or impossible to continue activity. The person may even have trouble walking with a normal gait, getting up from a seated position, or going down stairs.

Bruising and discoloration can be seen along the back of the thigh and occasionally, most comon with the more severe cases, there may be bruising along with palpable defects such as muscle lumpiness under the skin. These defects can be felt and seen with contraction.

-

Like with most musculoskeletal injuries, a patient history and physical exam performed by a healthcare professional will lead to an accurate diagnosis for acute hamstring injuries.

A clinician may determine the severity of the hamstring tear (grade 1 to 3) according to pain and physical limitations, including weakness and loss of motion. These findings may help estimate when a patient can return to activity.

Hamstring tears can be graded by severity:

Grade 1 is a strain of the muscle fibers

Grade 2 is a partial tear of the muscle

Grade 3 is a complete tear of the muscle

-

A clinician will ask the patient about how the injury happened, the location and pattern of pain, including how symptoms affect lifestyle and training/sports.

-

The clinician will use the physical exam to determine the location and severity of the injury.

A clinician conducting a physical exam may be able to use his or her hands to find where the injury is located; a hamstring tear will often cause a thickening and swelling of soft tissue. Palpation can often pinpoint the injury to either the muscle belly (myotendinous) or the high (proximal) hamstring.

The patient may be asked to perform various movements so the practitioner can evaluate strength and range of motion. Typically testing will be performed on both sides so that a comparison to the uninjured leg can be made to help gauge the severity of the injury.

Occasionally, the sciatic nerve (which runs down the back of the thigh) may become irritated or entrapped in healing scar tissue, causing sciatica-like symptoms down the leg. In this case, the physician will conduct a thorough musculoskeletal and neurologic examination. This is why it is important to have a healthcare professional perform a complete musculoskeletal and neurologic examination in the setting of hamstring strain.

-

Medical imaging tests are not needed in most cases. However, if the injury is severe, the diagnosis is uncertain, or a precise location for the injury is needed, imaging tests can be advantageous. Furthermore, in rare cases where there is significant loss of function or where surgery could help, it is important to determine the extent of injury to help guide treatment and possibly predict return to activity.

-

After an injury you may have heard from someone before about RICE (rest, ice, compression and elevation) when managing an injury. However, rest can be harmful and inhibits recovery. Recent research has now advised we use the acronym POLICE.

Protection

Optimal-Load

Ice

Compression

Elevation

The key term is Optimal-load, this replaces Rest. You may need to speak to your physiotherapist to discuss what your optimal load might be as it is specific to you but will help speed up your recovery process.

You can maintain your fitness using other forms of exercise that will not aggravate your hamstring, such as swimming, cycling or aqua jogging. You may need to speak to your physiotherapist to discuss what your optimal load might be as it is specific to you but will help speed up your recovery process.

If your injury is very acute it is now recommended that you DO NOT TAKE ANTI-INFLAMMATORY MEDICATIONS FOR THE FIRST 72 HOURS POST INJURY. This can affect the tissue healing.

-

It can be difficult to know when to start performing rehab exercises, especially when pain is present which can lead to fear avoidance behavior. As recurrence rates are high, patients often present with a lack of confidence in their ability (self-efficacy) to perform certain exercises or activities during rehabilitation due to fear of re-injury. You can discuss this with your healthcare professional to help maintain your motivation levels thus ensuring you return to normal activities and sport as soon as possible.

-

During the initial inflammatory phase of healing, the goal should be to control pain, decrease inflammation, and protect the muscle/tendon so scar tissue can develop. This stage may require crutches and taking weight off the injured leg in order to facilitate recovery, healing, and protection. You can gently bend and straighten as pain allows.

Avoid excessive stretching during this stage, because it may be detrimental to the recovery process.

The length of this phase depends on the severity of injury, but typically lasts 3 to 7 days. A qualified clinician should make decisions about progression to the next phase based on the patient’s clinical examination and function.

The Exercises

There are two protocols used for hamstring injury management based on the best, most recent evidence. They focus on eccentric training to address eccentric strength and tissue (fascicle) length. You can complete all 6 exercises as you feel able.

It is also normal to experience pain when completing the exercises, however this should not exceed 4/10 on a scale where 0 = no pain and 10 is the most severe pain you could imagine. By combining both protocols it will ensure a quick return to normal activity and sport, whilst reducing the risk of re-injury.

Askling L – Protocol

The extender (flexibility)

Starting position

The patient is lying supine, holding and stabilise the thigh of the injured leg with the hip flexed approximately 90°.

Instructions

The patient is instructed to perform slow knee extensions to a point just before pain is felt.

12 x 3, 2 x per day

Progression:

Increase speed.

The Diver (hamstring strength and trunk stability)

Starting position

The patient is standing with full weight on his injured leg and the opposite knee slightly flexed backwards.

Instructions

The patient is asked to perform the exercise as a simulated dive (hip flexion from an upright trunk position) of the injured, standing leg and simultaneous stretching arms forward and attempting maximal hip extension.6 x 3*Good quality, keep pelvis horizontally throughout the whole movement

*Maintain 10–20° knee flexion in the standing leg.

The Glider (Specific Eccentric Strength Exercise)

Starting position

The exercise is started with the patient positioned with upright trunk, one hand holding on to a support and legs slightly split. All the body weight should be on the heel of the injured leg with approximately 10–20° knee flexion.

Instructions

The patient is instructed to perform a gliding backward movement on the other leg and stop the movement before pain is reached. The movement back to the starting position should be performed by the help of both arms, not using the injured leg.

6 x 3Progression is achieved by increasing the gliding distance and performing the exercise faster.

A different Hamstring rehabilitation program, more recently developed is shown below. Initially all exercises are performed with both legs and progressed to one as tolerated. As it is essential to maintain high intensity, to achieve the desired adaptations, the exercises are only completed two to three times a week. You can add these to the Askling exercises and on the days without these you could do cardiovascular exercise, such as spinning or cross trainer work.

45° Hamstring Bridge

The patient is lying supine with arms placed in a comfortable position, knees flexed and foot on a step.

Instructions

The patient is instructed to raise their untested leg off the examination table and then perform repetitions of hip extension, where they push down through the heel of the tested leg and lift the hips off the ground towards full hip extension.Repeat 10 - 12 repetitions. Progress to doing it with one leg (affected leg). Aim for 8 repetitions 3 sets. To progress further you can hold weight to chest.

45° hip extension

Position thighs prone on padding of 45-degree hyper-extension apparatus. Hook heels on platform lip or under padded brace.

Instructions

Lower body by bending hips until fully flexed. Raise or extend hips until torso is parallel to legs.Repeat 8 – 10 repetitions. Progress to doing it with one let (affected leg). Aim for 6 -8 repetitions 3 sets. To progress further you can hold weight to chest

Eccentric Sliding Leg Curl

Begin in a supine position with heels positioned on sliding pads, or towel; in contact with slide board, or other suitable surface. Lift your hips into extension with the shoulders, hips, and knees aligned, and the ankles in a dorsiflexed position; creating stiffness throughout.

Instructions

Keep your elbows tucked in to your sides to help create a stable base of support to perform the movement. Slowly slide your heels out as far as you can keep controlled and return to starting position.

Repeat 6 - 8 repetitions 3 sets. Progress to doing it with one leg (affected leg). Aim for 6 -8 repetitions 3 sets. To progress further you can hold weight to chest and Nordics are introduced.

Nordics

Starting position:The patient is kneeling on either the Nordbord with ankles fixed or on a mat with the therapist or partner fixating the ankles.

Instructions:The patient is then instructed to fall forwards, and resist the fall to the ground as long for as possible using their hamstring muscle.

3 times per week1): 2x 5 reps

Drop only2) 2(3) x 5 – 8

Drop only3) 2(3) x 8 – 12, drop only4)

Repeat sessions 1-3 with drop AND curl

Return to Running

Many patients with grade one hamstring strains can return to light jogging quite soon after injury. The key aims here are to:

Avoid reproducing pain

Keep the effort easy

Gradually build up the volume of jogging (your mileage).

Allow adequate recovery between runs. Following a period of reduced intensity and the tissues need more conditioning (time) to return to normal and reduce the risk of re-injury.

One reliable way to return to running is through the national plan of ‘couch to 5k’.

For those who have missed less time away from training, they may be able to successfully return to running sooner and can push through the couch to 5k plan faster. As long as you follow the above guidelines you will have a successful outcome. Below are some exercises to do in-between to help on your return and also higher intensity/sport specific drills.

A/B skips

10 – 20m x 3 Sets

Runways: (Slider et al 2013)

After 5 minute warm up repeat each level 3 times, progressing to next level when pain free. Maximum 3 levels per session. Each phase progresses to reduced distance (measured in meters, m) to ensure progressive adaptation.On following session, start at the second highest level completed previously.

| Maximum speed 75% | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceleration (m) | Fly phase (m) | Deceleration (m) | |

| Stage one | 40 | 20 | 40 |

| Stage two | 35 | 20 | 35 |

| Stage three | 25 | 20 | 25 |

| Stage four | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Stage five | 15 | 20 | 15 |

| Stage six | 10 | 20 | 10 |

| Maximum speed 95% | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceleration (m) | Fly phase (m) | Deceleration (m) | |

| Stage 7 | 40 | 20 | 40 |

| Stage 8 | 35 | 20 | 35 |

| Stage 9 | 25 | 20 | 25 |

| Stage 10 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Stage 11 | 15 | 20 | 15 |

| Stage 12 | 10 | 20 | 10 |

Other things to consider

Return to Running

Passive knee extension = to the other side

Passive Knee flexion: 125+

Single leg squat (min of 60°): X5 from 20cm step, good control

Single leg bridge: At least 85% vs other leg = to or more than 30 secs

Single leg calf raises off step: At least 85% vs other leg = to or more than 20 rep

Side bridge endurance: At least 85% vs other side = to or more than 30 secs

Single leg sit to stand: At least 85% vs other leg = to or more than 10 reps (each leg)

Single leg balance: Eyes open > 43seyes closed > 9s

Single leg, leg press 1RM: 1.5 x BW

Squat 1RM: 1.5 x BW

Return to Sport

Once patients can run comfortably at 70% intensity they can return to sporting activities, which work below this. Unrestricted training is allowed when patients are able to tolerate sprinting and return to sport is started when two full pain free training sessions have been managed.